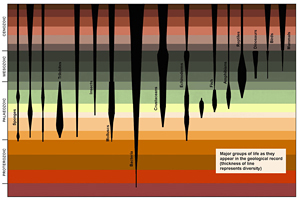

At the beginning of the Cambrian Period, within a span of a mere 10 million years, all the major groups of complex animal life, all the phyla, appeared. Ten million years may seem like a vast stretch of time: by most criteria it is a lot of time. But consider that nearly 3 billion years had already gone by since life had left its first traces in the fossil record. And consider, too, that no new phyla are known to have originated since the early Cambrian.

Here again we find a familiar pattern, on a truly grand scale: relatively suddenly, the whole spectrum of invertebrate life, including sponges, brachiopods, arthropods (trilobites, chelicerates and crustaceans), mollusks, plus spineless chordates in the same phylum as the vertebrates, burst on the scene, the world over. By the end of the Cambrian we have records for all the major groups of hard-shelled invertebrate organisms, and some evidence that vertebrates had appeared as well.

What could have caused such a proliferation?

Niles Eldredge, Fossils: The Evolution and Extinction of Species, 1991 (p 189).

The creativity represented by this invasion of novelty was so extravagant that there were more phyla in the Cambrian, at the beginning of the animal record, than at any future time, despite the fact that the entire evolutionary history of animals was yet to come. One locality where the conditions for preservation were exceptionally favourable, Chengjiang in South China, records no fewer than 18 phyla. Only one new phylum emerged after the Cambrian; many went extinct – which only adds to the sense of strangeness.

Organisms are classified according to their similarities, the lowest unit of classification being the species. Species comprise individuals that are most similar to each other. Typically, a small morphological gap separates one species from the next closest species. Species that are the most similar to each other are grouped into genera, then genera into families, families into orders, orders into classes, and classes into phyla. Not all phyla are so diverse as to include families, orders and classes. A single species may constitute a phylum all by itself if no other species share its distinctive design features.

Such a scheme is reasonably understood to reflect degrees of genealogical (evolutionary) relationship. Over time species multiply and diversify, with the result that recent species are more similar to each other than to older species. Gaps between the groups increase as one ascends the hierarchy, while the number of groups decreases: classes, for example, differ more than orders do, and phyla differ more than classes. That said, the greater the morphological and molecular differences, the more one needs to ensure that solid evidence supports the assumption of genealogical relationship. Otherwise the gaps may be evidence of non-relationship.

The theory of evolution assumes no limits. When phyla are grouped together into kingdoms and kingdoms into domains (eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea), the assumption is that all organisms are related, no matter how different. All organisms are celled. Eukaryotes comprise all organisms whose cells contain a nucleus, namely animals, plants, fungi and protists. Most are multicellular, a few, such as amoebas, are unicellular. A few single-cell organisms have more than one nucleus. Bacteria and archaea consist of one cell but have no nucleus. Bacteria and archaea are single-celled and have no nucleus. Archaea, whose architectural distinctiveness was recognised only in 1977, differ radically from bacteria. Among their differences is the way they package their DNA into flexible coils, enabling the information to be accessed without the need for special proteins (Bowerman et al. 2021). Differences do not mean that once, at a deeper level, there were none. One cannot logically conclude from the fact that only some organisms have nuclei that they evolved from those without nuclei. Generalisation at this level is absurdly simple-minded.

The ultimate step in this reductive chain of reasoning is to postulate that these three domains arose from an entity called the ‘last universal common ancestor’, or LUCA, which no longer exists. Whether it ever existed is something evolutionary biologists themselves struggle with. Archaea and bacteria are genetically so different that any such ancestor would have had to have more genes and metabolic capabilities than either of them, a kind of super-cell whose existence would only aggravate the problem of how the LUCA itself evolved into being. Some propose that the tree of life be replaced by a circle, or a network (Katz et al. 2021). Archaea and bacteria, on the other hand, do still exist, and they are not mere evolutionary leftovers. They play a vital role processing and recycling nutrients at all levels of the biosphere. Without bacteria we would not be able to digest food. No bacteria, no life! Even on the skin, bacteria, fungi and archaea communicate with immune cells and with each other to keep the skin healthy and ward off pathogens.

If there is a limit beyond which genealogical relationship ceases to be plausible, where might that be? In most cases, the largest grouping suggestive of common ancestry is the phylum. Phyla do not branch into other phyla. If some classes within a phylum differ so radically that they seem almost to contradict this statement, their bifurcation is invariably abrupt, not evolutionary, controlled, not haphazard. Organisms within the phyla are united by a body plan or architectural design fundamentally unlike other body plans, and throughout the fossil record that distinctiveness persists. They are the same today as they were in the Cambrian. Phyla can be groups with other phyla only by seeking similarities at the level of body plan construction: whether the embryo begins with two germ layers or three, whether the mouth or the anus forms first, whether an animal’s body is radially or bilaterally symmetrical. The distinctive plan dissolves and one is left with uninformative generality.

Invertebrates can be classified into some 35 basic body plans, ignoring extinct phyla and not counting separately the components of the superphyla Chordata (lumping together, questionably, all vertebrates, plus tunicates and lancelets) and Arthropoda (the biggest grouping of all, lumping together trilobites, onychophorans, anomalocarids, chelicerates, crustaceans, myriapods, insects and spiders). In the context of Darwinian evolution, complex ‘basic body plans’ are not predicted, least of all at the beginning of the fossil record. Theory postulates that life started with minimal complexity and became more complex gradually, whereas animals, at both the macroscopic-morphological and microscopic-molecular level, have always been complex. This is because animals move, and locomotion requires a locomotor system (muscles, ligaments, tendons and the like), a nervous system capable of sensing the environment, energy produced by digestive and respiratory systems, an excretory system, organs that sense and focus light, and a brain (usually, not always – only adding to their mystery, echinoderms, hemichordates, jellyfish, comb jellies and roundworms move but have no brain). And all these systems are mutually dependent – the eyes on the brain, the brain on the heart, and so on, and all depend on the vessels that circulate oxygen round every part of the body. Without the ability to move, an animal cannot feed. Without a digestive system, it cannot turn food into energy.

Not all animals have a cardiovascular system, but consider those that do. Was this an ‘optional extra’ that evolved little by little, piece by piece? The common-sense answer is ‘of course not’. It is implausible to suppose it could have been the product of mutations haphazardly accumulating one by one, without coordination. But the scientific answer is also ‘no’, for the fossil of one Cambrian arthropod, Fuxianhuia, is sufficiently well preserved for us to discern the same segmental organization of lateral vessels, the same ‘broad dorsal vessel extending through the thorax to the brain where anastomosing branches overlap brain segments and supply the eyes and antennae’, as we see in insects, spiders, scorpions and horseshoe crabs today (Ma et al. 2014). Arthropods were already anatomically advanced at the beginning of their fossil record.

The phyla, likewise, that have eyes now had eyes then. Whether legged or swimming animals, they needed them to navigate. Among the earliest known vertebrates, the fish-like Haikouichthys had four eyes, not two, as long supposed – four camera eyes, with lens, retina and iris, like our own. Did vertebrates start with four and then dispense with two of them? As a commentary accompanying the report noted, such ‘findings upend conventional views of eye evolution’; in reality ‘evolution often moves towards less complexity rather than more’.

Chaetognaths (meaning ‘bristle jaws’ but commonly known as arrow worms) are the most abundant planktonic predators alive. Fossils from Canada’s Burgess Shale (~508 Ma) show a remarkable resemblance to modern chaetognaths. Other chaetognaths from the Cambrian had camera eyes, but on stalks. Modern chaetognaths do not have camera eyes. They have light sensors, which cannot form clear images. Information about their environment and prey is adequately communicated through their hairs and bristles, even enabling them to hunt in darkness. Were these light sensors the evolutionary forerunners of the camera eyes? That’s hardly likely. Camera eyes did not confer a long-term evolutionary advantage; they proved an unnecessary expense. Rather, the two types of chaetognath, those with lenses and those without, seem to have diverged from their common ancestor simultaneously. Worse still, in the theory of evolution chaetognaths and vertebrates evolved camera eyes independently. So, within their respective phyla, must cephalopods within Mollusca, alciopid worms within Annelida and box jellyfish within Cnidaria.

Trilobites, it is said, ‘possessed the most sophisticated eye lenses ever produced by nature’ (Shawver 1974). They knew about Fermat’s principle, about Abbe’s sine law, about Snell’s law of refraction and about the optics of birefringent crystal. One arthropod had stalked eyes consisting of over 2000 lens facets (Zhao et al. 2013). The compound eyes of another Cambrian arthropod had over 3000 lenses (Lee et al. 2011). Anomalocaris had over 24,000. In these cases, the size gradient of the lenses created a distinct ‘bright zone’ where the visual field was sampled with higher light sensitivity – as observed in modern dragonflies’ eyes. Consider how much brain power was needed to process even just 2000 images, continually changing as the animal moved about. The genetic programs that constructed all this complexity had to have been no less complex.

Have you ever wondered why you have two eyes and not any other number? Why they feature side by side, just in front of the seat of consciousness, which experiences everything as if through the eyes? Two eyes in front of the head, say the ideologues, were inherited from the apes, and stereoscopic vision conferred a reproductive advantage: animals born with eyes placed further forward had more progeny. But this is a ‘just so’ story, assuming that there has to be an evolutionary reason. In fact, animals with two forward-placed eyes go all the way back to the Cambrian, some with compound eyes, some with simple eyes.

The fossil record suggests that the major pulse of diversification of phyla occurs before that of classes, classes before that of orders, and orders before families. … The higher taxa do not seem to have diverged through an accumulation of lower taxa.

Evolution 41, 1177–1186 (1987)

When the phyla first appeared, they were already differentiated into classes. Cnidarians were already differentiated into Hydrozoa, Anthozoa (comprising already differentiated corals and anemones), Cubozoa (box jellyfish) and Scyphozoa (other jellyfish). Molluscs were already differentiated into Gastropoda, Bivalvia and Cephalopoda (amongst others), represented today by whelks, scallops and octopuses; the first cephalopods even had jet propulsion. Brachiopoda – a type of shellfish – already encompassed eight classes in the Cambrian: Lingulata, Phoronata, Craniata, Chileata, Obolellata, Kutorginata, Strophomenata and Rhynchonellata. These radical pre-programmed re-organisations within the basic plan must have taken place invisible to the fossil record during the Precambrian. Evolutionary history after the Cambrian – the origination of orders and a few further classes within the phyla and of many new species within the already established classes – was minor in relation to what went before.

Of course, if we abandon the presupposition of interrelatedness and instead suppose that all the body plans were present from the beginning, what we are left with is a problem of timing. A long stretch of time preceded the Cambrian, during which bacteria, algae and ‘acritarchs’ (unidentified microscopic plankton but mostly the resting cysts of algae) are well attested. Although they eluded fossilisation, animals also must have existed. Ancestors of the brachiopods, tunicates, onychophora, chelicerates, crustaceans, molluscs, cnidarians, comb jellies, arrow worms, echinoderms, hemichordates, bryozoa, flatworms, roundworms, segmented worms, spiny-headed worms, radiolarians, loricifera and chordates, not to mention the phyla that became extinct, must have existed somewhere and in some form for at least as long as bacteria and algae did.

According to the biblical tradition, the original ocean lay beneath the land (see The antediluvian world). Lakes may have existed at surface level, but since all terrestrial surfaces were destroyed in the Cataclysm, the only aquatic creatures likely to have survived would have been those living at great depth, in the dark. Indeed, a great variety of animals and other organisms still live below the 200-metre-deep zone through which light penetrates.

Following the Cataclysm, seafloor spreading and thus the generation of ocean crust was orders of magnitude faster than now, because heat-producing radioactive elements were more abundant and their rate of decay much higher. Consequently, even though the Sun was giving out less heat, oceans were warmer. Some estimates suggest average temperatures in the Archaean above 60 ?C. Submarine volcanism spewed out large volumes of iron, manganese and sulphur, making all but the uppermost layer of the ocean anoxic and poisonous to animal life. Photosynthesising cyanobacteria kept the surface habitable by producing oxygen, which reacted with the dissolved iron, manganese and sulphur to precipitate insoluble oxides. These then sank and allowed the oxygen not consumed by the reactions to remain available for animal organisms. Since oxygen solubility decreases with temperature, most of the gas escaped into the atmosphere. Nearly all marine animals will have been confined to the cooler poles.

- the coastal waters were no longer toxic

- oxygen levels at the seafloor were high enough

- the seas had sufficiently cooled

were either jellyfish or ctenophores (comb jellies), dating to soon after 600 Ma. Though they belong to different phylum, ctenophores and jellyfish can be difficult to tell apart. Claims that slightly younger fossils were microscopic embryos are disputed. Then, around 575 Ma, a strange assortment of soft-bodied multicellular organisms appears, known as the Ediacaran Biota. They show up about the same time in many parts of the world, from the Ediacara Hills of Australia to Charnwood Forest in England, initially in deep-water settings. By 555 Ma they had migrated to the shallower shelf (Boag et al. 2018). Some were unattached, feeding on microbial mats; some, frond-like in appearance, were fixed to the seafloor by holdfasts and connected to each other by filaments up to metres long, possibly indicating that they reproduced by cloning. Some had a spiral form, others a triradial symmetry, or a fractal pattern. Where to place them in the tree of life no one knows. They appear to comprise multiple phyla unrelated to later organisms, and most became extinct before the Cambrian. One fossil, the bilaterally symmetrical, leaf-like Dickinsonia, is associated with the remains of cholesterol, reportedly only found in animals. Either Dickinsonia was an animal, or it is evidence that cholesterol does not occur only in animals (which is true). It could slowly shift position, but had no discernible legs, eyes, mouth or gut, and it does not resemble any Cambrian animal. Kimberella had a gut and fed on algae and bacteria.

were either jellyfish or ctenophores (comb jellies), dating to soon after 600 Ma. Though they belong to different phylum, ctenophores and jellyfish can be difficult to tell apart. Claims that slightly younger fossils were microscopic embryos are disputed. Then, around 575 Ma, a strange assortment of soft-bodied multicellular organisms appears, known as the Ediacaran Biota. They show up about the same time in many parts of the world, from the Ediacara Hills of Australia to Charnwood Forest in England, initially in deep-water settings. By 555 Ma they had migrated to the shallower shelf (Boag et al. 2018). Some were unattached, feeding on microbial mats; some, frond-like in appearance, were fixed to the seafloor by holdfasts and connected to each other by filaments up to metres long, possibly indicating that they reproduced by cloning. Some had a spiral form, others a triradial symmetry, or a fractal pattern. Where to place them in the tree of life no one knows. They appear to comprise multiple phyla unrelated to later organisms, and most became extinct before the Cambrian. One fossil, the bilaterally symmetrical, leaf-like Dickinsonia, is associated with the remains of cholesterol, reportedly only found in animals. Either Dickinsonia was an animal, or it is evidence that cholesterol does not occur only in animals (which is true). It could slowly shift position, but had no discernible legs, eyes, mouth or gut, and it does not resemble any Cambrian animal. Kimberella had a gut and fed on algae and bacteria.

One or two fossils do suggest animal affinities. Arkarua may have been an early soft-bodied echinoderm. Uncus, from 555 Ma, was a nematode-like worm. As we approach the Cambrian period (539–487 Ma), we see the first evidence of animals’ definitive property of voluntary movement, in the form of trails left by deposit-feeding worms along the sediment surface. The stumpy Ikaria, 1-1.5 mm wide (smaller than a grain of rice), may have been a burrower. Yilingia had a segmented body up to 27 cm long but seems to have remained at the surface. Vertical burrowing was extremely rare.

The first mineralised skeletons and armour also appear about this time. Their collective name, ‘small shelly fauna,’ reflects the fact that most are only millimetres in length and not easily identified. Many seem to be fragments of larger animals such as brachiopods and echinoderms. One of the better known examples, Cloudina, formed extensive reefs consisting of tube-like stacks of nested cones. One function of the shells was to protect against predation. Borings show that unknown carnivorous predators had already evolved the ability to overcome these defences. Sponges – which are animals – initially had organic rather than mineral skeletons: for example, Helicolocellus, reconstructed as having a goblet-shaped body more than 40?cm in height.

Rocks susceptible to radiometric dating being relatively rare, time-zones are generally determined by the fossils characterising them. Thus the boundary between the Precambrian and the Cambrian is defined by the first appearance of the burrow Treptichnus pedum, probably made by a priapulid worm. This is not a true time-line. Most of the places where the fossil appears lack datable rocks and, where such rocks exist, the dates do not always agree. In Oman the boundary is dated to 541 Ma, in Namibia to 538.7 Ma, more than 2 Ma later. In Nevada the Precambrian/Cambrian boundary is radiometrically dated no earlier than 533 Ma (Nelson et al. 2023), but small burrows similar in form to those characteristic of Cambrian strata occur over 500 m below the boundary. Unusually, the Treptichnus animal was a generalist, living in both deep-water and shallow-water settings on the shelf. Whether it left evidence of its presence was a matter of chance.

The dating problem is systemic. The lower-to-middle Cambrian is the only interval in the entire Phanerozoic where it proves impossible to correlate strata on different continents using fossils. The animals were not evolving fast enough at the species level, and their occurrence depended too much on accident, on the right conditions for their suddenly colonising a seabed and subsequently becoming entombed. We cannot assume that the occurrence of the same trilobite or sponge species marks the same interval everywhere. The problem is exacerbated by the multimillion-year timescale, requiring 8 million years for Nevada’s faunal assemblage to catch up with Oman’s, for instance. Even a time-lag of 10,000 years would be difficult to swallow.

Trilobites appear around the world more or less simulaneously around 521 Ma, and already they differ from each other – not just at the species but at the family level. TThis is 16 Ma after their burrows, Cruziana, appear. Even if they had had soft exoskeletons, here and there their bodies should have left fossils. By the time they do appear, they already differ from each other – not just at the species but at the family level – and the period of greatest and most rapid evolution is over.

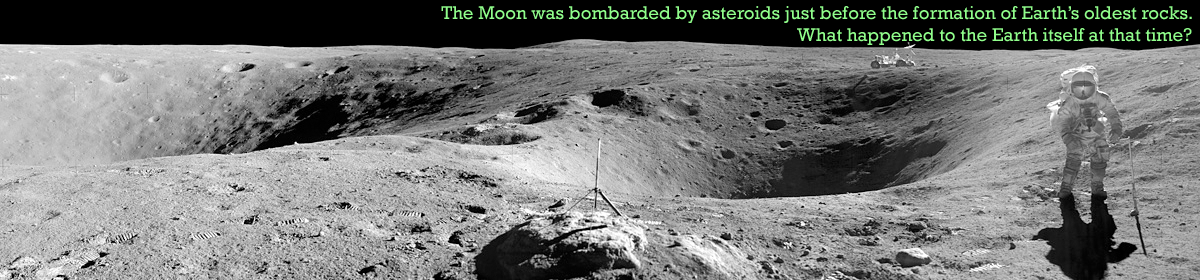

Things were also changing on the plate tectonics front. What is now South America and Africa was amalgamating, while the break-up of the supercontinent called Rodinia was coming to an end. The dispersing continents – North America (including Scotland), Baltica (northern Europe) and Siberia among others – shifted from their various latitudes in the southern hemisphere to latitudes either side of the equator. As parts of the microcontinent Avalonia, England and Wales during the Cambrian and Ordovician migrated from around 60° S to 40° S. Undersea magmatism was creating the buoyant floors of new oceans and causing sea-levels to rise. The margins of the dispersing continents flooded, to produce vast, shallow, epicontinental seas, far removed from the still hot, toxic, and largely anoxic global ocean. Such isolation enabled shallow waters to reach a new equilibrium with the oxygen-rich atmosphere. The area of habitable marine environments surged. At the same time, the zones of upwelling where the deep sea met the shelf dredged up huge quantities of phosphorus, a vital nutrient that is depleted in the upper ocean, and spread it onto the platforms. Thanks partly to exceptional conditions of preservation, phosphate deposition peaked in the early Cambrian.

This is the significance of the ‘Great Unconformity’ displayed near the bottom of the Grand Canyon, where variably tilted volcanic and sedimentary rocks of Meso- and Neoproterozoic age were planed off as if by a giant saw. Above the unconformity lie horizontal strata of continentally sourced shales and quartz-rich sandstones, deposited in the Cambrian after an interval of extraordinary erosion. Carbon dioxide escaping from submarine rifts acidified the encroaching flood waters, so that the cement between sedimentary grains dissolved and the rocks disintegrated. As a result, huge quantities of calcium entered the ocean, at the same time as elevated rates of seafloor spreading bound up more of its magnesium. In the period 550 to 515 Ma the Mg/Ca ratio of seawater plunged, from 6.1 to 1.2. Alkalinity, in part a function of the Ca and Mg ions in the water, recovered, rising to levels higher than at any other time in the Phanerozoic, allowing thick accumulations of limestone to precipitate, only a small proportion of which consisted of shells. By the early Ordovician, most of North America was flooded. Sea-levels globally were high. The marine communities which we know about occur on the flooded continents, not ocean crust.

The Great Unconformity can be seen in many parts of the world, along with the same sequence of rocks: a basal conglomerate, then quartz-rich sandstones, glauconitic sandstones, shales and finally limestones (Ager 1981). That does not mean that the associated erosion was everywhere synchronous, nor that a time gap exists everywhere below the Cambrian. Indeed, where there is no gap, the point at which one crosses into the Cambrian is often far from clear. Chronological boundaries after the Cambrian are defined by the earliest appearance of organisms (‘index fossils’) that were both wide-ranging and short-lived, on the basis that they colonised the globe from their regions of origin more rapidly than radiometric dating has the power to distinguish, and they either rapidly evolved into some other species or died out. At the beginning of the Cambrian, fossils are rare. Even higher up there are no widespread, rapidly evolving organisms to provide a basis for correlation between continents (Zhang et al. 2017). So far as the visible record is concerned, the Cambrian Explosion does not really get underway until about a fifth into the period, around 530 Ma. Niles Eldredge’s ‘mere 10 million years’, taking us to 520 Ma, is therefore about right.

Evidently the animals which brought about the Cambrian revolution did not come into being ex nihilo. But nor did they evolve from the Ediacaran organisms before them: they are too different, and the interval between them too short, for slight, successive modifications to have brought about the implied transformations. One might just as well believe in natural magic, as in practice all palaeontologists do. More viable explanations for the apparent absence of ancestors are: (1) the animals were too few in number to have made a mark on the fossil record, (2) they lacked fossilisable hard parts, such as bones, or shells, and (3) they were mobile rather than sessile, swimming close to the surface, and at death dissolved soon after they reached the bottom. The first factor is untestable and raises the question why, in the mid Cambrian, there was such an increase in numbers; it will not be discussed further. The second also has little explanatory power, but is relevant to the third factor, the possibility that changes in the marine environment, affecting nearly all phyla, triggered a fundamental change in behaviour and physiology.

In providing support for delicate organs and tissues, shells and skeletons are very necessary for animals above a certain size. Initially animals were soft-bodied. That much is obvious, for otherwise they certainly would have hit the fossil record. Soft parts quickly decay or get devoured, so rarely get fossilised. But ‘rarely’ is not never, and there were times and places before the Cambrian when soft parts did get preserved. But not, until the very end, the bodies of animals. With the Cambrian that changed. Almost as soon as jellies and worms were becoming fossilised, other marine animals were suddenly acquiring shells and skeletons. This was happening across the board. Most constructed them out of minerals already present in the water, such as calcium carbonate (itself consisting of two forms, calcite and aragonite), calcium phosphate, and silica. Arthropod phyla made their hard parts out of proteins and chitin. Palaeontologists refer to this revolution as ‘biomineralisation’. That it occurred at the same time as the Cambrian Explosion cannot have been a coincidence.

As we have noted, calcium concentrations in the epicontinental seas rose dramatically through the early and middle Cambrian. It is of course easier to secrete calcium carbonate (assuming you already have the ability) when calcium concentrations are high. During times of high Mg relative to Ca (higher than 2), the mineral takes the form of aragonite; during times of low Mg/Ca, it precipitates as calcite. The threshold was crossed around 525 Ma. Before then, animal classes that secreted shells made them out of aragonite or calcium phosphate. The majority waited until after 525 Ma, when they made them out of calcite. Their responses were programmed responses.

After the Cambrian, the most striking instance of delayed biomineralisation is the late appearance of modern corals, order Scleractinia, within the class Anthozoa and phylum Cnidaria. Two large orders of corals had acquired skeletons already in the Ordovician, but at the end of the Permian they became extinct. Scleractinians – which have aragonite skeletons – did not hit the fossil record until the following period, in the mid Triassic, by which time they comprised three suborders and nine or ten families. The most plausible explanation for their absence is that they originated as soft-bodied forms in the Ordovician, about the same time as the other two orders. Since ocean calcium carbonate saturation decreases with depth, during the Palaeozoic they may have been restricted to the deep sea beyond the continents and only began to migrate to shallower levels later.

If phyla were all related to each other and evolution was a chance process, one would expect the genetic instructions for making carbonate skeletons to have evolved (somehow) just once, after which the biomineralising and non-biomineralising groups went their separate ways. The prediction can be tested, for phyla are grafted into the imaginary tree of life according to how similar their DNA and developmental pathways are, factors that probe relationships at a much more fundamental level than whether they biomineralise. What one finds is that biomineralisers are scattered irregularly through the tree (Murdock & Donoghue 2014), that the instructions for making hard parts had to have arisen independently at least 14 times. Phosphatic skeletons are thought to have evolved more than 10 times just within the early Cambrian (Bengtson & Conway Morris 1992). One phylum – the sponges – had the ability to commandeer all three minerals: silica, calcite and phosphate. So which scenario is the more likely, that the same biological instructions evolved multiple times and more or less simultaneously by chance, or that the different lineages were created with those instructions? Since in the former scenario chance has just the same limitless inventiveness, and the same invisibility, as a supernatural Creator, what we are really offered is a disguised self-contradiction, an insidious deceit.

In most cases, we become aware of a class or phylum at the point it began to biomineralise. One moment the group was invisible to the fossil record, the next, its members had shells and skeletons, as if the genetic instructions to form them were switched on as one system in the organism and about the same time in all species. From the moment trilobites appeared, every part of the skeleton was mineralised, as were the calcite lenses of their eyes. In response to hormonal signals they already had the ability to moult, sloughing off their old carapaces along predetermined suture lines, and in their place to grow bigger ones, together with additional thoracic segments.

Despite their morphological differences, , a thing that nearly all marine invertebrate phyla have in common above a certain size is that they start off as larvae: tiny, usually soft-bodied swimmers. Only after miraculously metamorphosing into an entirely different form do they restrict themselves to life on the seafloor. Just as ‘basic body plans’ are not predicted in Darwinian evolution, nor is it predicted that nearly all phyla have at least two body plans, the larva being as distinct as the adult. Sponges, molluscs, the various worm phyla, cnidarians (e.g. corals), echinoderms, brachiopods, tunicates (a subphylum within the chordates) and loricifera (microscopic sediment-dwellers resembling stalk-filled vases) all have a larval stage, and the larvae are bewilderingly diverse (Hejnol & Vellutini 2017). In the case of the larvae of nemertean worms, the juvenile develops inside the larva from a series of isolated rudiments and consumes the body.

Despite their morphological differences, , a thing that nearly all marine invertebrate phyla have in common above a certain size is that they start off as larvae: tiny, usually soft-bodied swimmers. Only after miraculously metamorphosing into an entirely different form do they restrict themselves to life on the seafloor. Just as ‘basic body plans’ are not predicted in Darwinian evolution, nor is it predicted that nearly all phyla have at least two body plans, the larva being as distinct as the adult. Sponges, molluscs, the various worm phyla, cnidarians (e.g. corals), echinoderms, brachiopods, tunicates (a subphylum within the chordates) and loricifera (microscopic sediment-dwellers resembling stalk-filled vases) all have a larval stage, and the larvae are bewilderingly diverse (Hejnol & Vellutini 2017). In the case of the larvae of nemertean worms, the juvenile develops inside the larva from a series of isolated rudiments and consumes the body.

Some larvae go through more than one stage. In the case of barnacles, the first stage, called the nauplius, has a thin calcareous shell and a single eye, and moults five times – itself a remarkable phenomenon – before transforming into the cypris. The cypris looks for a suitable place to settle. Having made its choice, it cements itself to the surface and metamorphoses into the barnacle adult, hedged round with calcareous plates. Some larvae can delay metamorphosis indefinitely until they encounter a suitable substrate (Young 1999). ‘Suitable’ might be sediment of a particular grain size or texture, or one already occupied by individuals of the same species. To avoid predation, many larvae rise towards the surface at night and seek deeper water during the day. As they grow, they become less responsive to light and gravitate towards the floor.

Larval metamorphosis occurs when neurosensory cells detect a specific environmental cue and stimulate the release of chemicals into the nervous system (Ueda et al. 2016). These then activate a cascade of signals which induce the larva to settle and begin the transformation into an adult. Signalling systems vary, but in most invertebrates internally synthesised nitric oxide plays a key role. Metamorphosis is repressed when synthesis of the gas is high, promoted when it drops.

Metamorphosis is pre-programmed transformation of the individual: about as unambiguous a display of the power of the Creator as one could imagine. Just as ‘basic body plans’ are not predicted in Darwinian evolution, nor is it predicted that nearly all phyla have at least two body plans, the larva being as distinct as the adult. How could ‘numerous, successive, slight modifications’ (Darwin’s phrase), each occurring by chance, have given rise to such programming? How could they each have constituted an advantage in relation to a transformation that was all or nothing? Anything along the way would not have been viable – precisely why the transition from larva to adult is kept as brief as possible. And why was the larval stage not left behind in the course of evolution? Species may occasionally lose the larval stage, but in all other cases the larval stage remains obligatory.

The absence of penetrative burrows more than a few Ma before the Cambrian strongly implies that the ancestors of worms and trilobites lived above the sediment. They were larval, and did not get fossilised because the environment was giving signals inhibiting them from settling and metamorphosing. Inasmuch as they must have been able to reproduce, modern analogues would include larvaceans, a non-metamorphosing group within tunicates, and certain salamander species that become sexually mature as larvae and do not metamorphose. Some lineages ‘re-evolved’ metamorphosis after losing the larval stage (Chippendale et al. 2004), as if a dormant program was re-activated.

Very occasionally, as at Qingjiang, unclassifiable ‘submillimeter- to millimetre-sized, delicate, larval or juvenile forms’ did get to be fossilised. As with most instances of soft-body preservation, episodic turbidity flows transported them downslope to levels where the lack of oxygen inhibited decomposition. Here is the summary of a report of an early Cambrian find (Zhang et al. 2010):

A new eucrustacean arthropod, Wujicaris muelleri, is represented by a Lower Cambrian early metanauplius of strikingly modern morphology despite being the oldest known fossil of such an early immature crustacean larva. The morphology closely mirrors that of corresponding developmental stages of living barnacles and copepods, and it is likely that its appendages had a similar function for feeding and locomotion. The larva demonstrates remarkable stasis in morphology, life history, and lifestyle of (small) eucrustaceans over 525 million years.

In addition, we know of a few non-mobile taxa from the latest Precambrian that were soft-bodied in clastic environments but skeletonised in carbonate environments (Wood et al. 2017).

Metamorphosis and the development of hard parts are likely to have gone hand in hand. Some larvae today have been observed to grow calcareous skeletons prior to metamorphosis, providing ballast that enables them to sink, and we know that trilobite larvae had calcareous shells. In nearly all cases where the adults are biomineralised, they acquire their hard parts as the animals metamorphose.

The main environmental cue for the transformation would have been higher levels of oxygen in the water. The larger body size and complex musculature of the biomineralised adult required more energy. Carbonate rock sequences in which we can trace fluctuating oxygen levels show that small skeletal organisms preferred waters that were well-oxygenated. Large skeletal organisms solely lived in such conditions (Tostevin et al. 2016).

Before 550 Ma the sea bottom was not a habitable place. Because of the high rates of volcanism driving seafloor generation, the oceans were thermally and chemically stratified. Bottom waters were warmer than surface waters because they carried large amounts of dissolved iron, making them denser, while the high volumes of degassing CO2 associated with the volcanism made them acidic. Fossilisation is always a race against the chemical and biological agents that promote decay, but corpses sinking through the water column would have begun dissolving even before they reached the bottom. The exquisite preservation of soft tissues in ‘Burgess Shale-type’ deposits of the early and middle Cambrian was due to animals being swept from their oxygenated waters into the downslope intermediate zone, at 50–100 m depth still on the continent, where the waters were anoxic but neither alkaline nor acidic. Oxygenated sulphur – sulphate – reacted with the dissolved iron and got sequestered in the form of pyrite (FeS2), so that even the decomposing activity of anaerobic sulphate-reducing bacteria was inhibited. The intermediate zone was a preservational sweet spot: too little oxygen for the presence of scavengers and decomposing microbes, but rates of sediment deposition high, as episodic turbidity currents transported mud particles and uprooted the newly established fauna from their habitats upslope.

The burrowers around the beginning of the Cambrian were ecological pioneers. Faecal pellets dropped by zooplankton attracted sediment-dwelling animals that grazed on them, and as they did so, they churned up the sediment, aerated it and fertilised it. This, in turn, enabled other burrowers to live in and feed off greater depths of sediment. Conversely, oxygenation helped buried organic matter to decompose and buried phosphate to be recycled. Low rates of deposition were another prerequisite. The chances of survival were slim if the seafloor was no sooner colonised than buried. Barren seafloors were turning into habitable environments for almost the full range of seafloor-dwelling organisms.

The burrowers around the beginning of the Cambrian were ecological pioneers. Faecal pellets dropped by zooplankton attracted sediment-dwelling animals that grazed on them, and as they did so, they churned up the sediment, aerated it and fertilised it. This, in turn, enabled other burrowers to live in and feed off greater depths of sediment. Conversely, oxygenation helped buried organic matter to decompose and buried phosphate to be recycled. Low rates of deposition were another prerequisite. The chances of survival were slim if the seafloor was no sooner colonised than buried. Barren seafloors were turning into habitable environments for almost the full range of seafloor-dwelling organisms.

Marine organisms appeared successively – first phytoplankton (the photosynthesising primary producers), then zooplankton, then seafloor-dwelling herbivores and immobile filter-feeders, then swimming and seafloor-dwelling carnivores and deposit-feeders, and finally large predators. Sessile organisms such as sponges and corals themselves modified their environments by building reefs, creating ecological niches for other organisms. At all levels of the ecological pyramid species multiplied at the same time as the ecological levels multiplied. Some, such as sea-lilies and bryozoans, encrusted the floors called hardgrounds, where sedimentation had paused long enough for the surfaces to become cemented, until renewed deposition smothered the animals. The explosive appearance of marine life was a staggered rather than instant phenomenon. In the mid Cambrian marine animal life was mostly restricted to habitats in and immediately above the seafloor; by the Ordovician almost the entire water column was filled with organisms. This is the true meaning of the order of fossils at this time. Organisms higher up the food chain depended on those lower down and were not programmed to reproduce as numerously. The development of complex communities took time.

Food webs in the Cambrian were ‘remarkably similar’ in structure to modern food webs (Dunne et al. 2008). Fundamentally, marine food chains changed little over time, just as, fundamentally, the organisms that composed them changed little. The disparate organisms that appeared in the Cambrian were linked by food chains, not evolutionary chains. There is no evidence that zooplankton evolved from bacteria, or that worms, molluscs, sponges and so on evolved from zooplankton.

Food webs in the Cambrian were ‘remarkably similar’ in structure to modern food webs (Dunne et al. 2008). Fundamentally, marine food chains changed little over time, just as, fundamentally, the organisms that composed them changed little. The disparate organisms that appeared in the Cambrian were linked by food chains, not evolutionary chains. There is no evidence that zooplankton evolved from bacteria, or that worms, molluscs, sponges and so on evolved from zooplankton.

Darwin’s theory requires the evidence of ‘numerous, fine, intermediate, fossil links’. Darwin imagined that in the vast ages before the Cambrian the world must have ’swarmed’ with living creatures. But what we find is revolution, not evolution: an explosion of life forms as continental margins flooded and began to be colonised by phyla that must have pre-existed, invisibly, as tiny soft-bodied organisms in the open sea – immigrants, it seems likely, from high-latitude regions. For thousands of years the margins, to all appearance, had been barren of animal life. Now the time, always foreseen, for orchestrated colonisation had arrived. Starting with sediment-churning worms and climaxing with sharks, it was a staged ecological progression, unfolding over a thousand of years, not three thousand million. Large areas of continent flooded and species responded to a variety of factors: an increase in nutrients released by continental erosion, an increase in dissolved calcium, an increase in seawater oxygen. The response was to metamorphose from tiny larvae to much larger adults, to biomineralise, to take up a settled existence on the seafloor, to prey on others that had done so. It was only when thrown into close proximity with each other that organisms began to compete. Environments multiplied, dividing into ever finer ecological niches, and as they multiplied, so did the species that filled them. Species multiplied in situ, leading, in the Ordovician, to more provincial distributions of fauna. Deeper levels of the sea – the ocean beyond the continental shelves – became inhabited as gradually they too, in succeeding periods, became cooler and more oxygenated.