The order in which fossils appear over time can be understood in one of four ways. This article summarises the various interpretations.

(1) To begin with the most familiar: Charles Darwin pioneered the idea that, somehow, life arose naturally and that successively more complex forms evolved as a result of chance mutations. In graphic representation, and updated in accordance with current nomenclature, the interpretation looks like this:

Natural selection acts only by the preservation and accumulation of small inherited modifications. If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.

The Origin of Species, 1859.

Darwin felt he could imagine a finely graduated series of forms meandering from, say, no eye at all to the complex eye of an octopus or eagle, and since he could imagine them, it seemed reasonable to suppose that they might have happened. Given enough time, chance processes might have produced an appearance of exquisite design. Still, although he laid the burden of proof on those who doubted his theory, the ultimate test lay with the fossil record. The question was whether life had evolved from simple to complex, not merely whether it could have.

Why then is not every geological formation and every strata full of such intermediate links? Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely-graduated organic chain; and this, perhaps, is the most obvious and serious objection which can be urged against my theory.

He put the lack of corroboration down to the records being inadequately known. One hundred and fifty years later, that explanation will not serve. Although the record is now well sampled, it still does not reveal the expected pattern. Some lineages show gradual evolutionary change, others jerky change, including a number of truly amazing transformations. What palaeontologists have not been able to trace is a single genealogical tree beginning with simple organisms in the sea and ending with an array of complex organisms on land. Organisms appear to have had multiple ancestries. Despite billions of research dollars spent on trying to link them all together, Darwin’s audacious idea has not delivered.

A variant of this view – espoused by nearly all academics who profess a Christian faith, despite its failure to deliver – is that God ‘guided’ the process of evolution, or that the Big Bang resulted in a universe so finely tuned that even without divine guidance evolution was able to produce the world we live in now. That was how God chose to achieve his purpose. ‘Evolution is the method by which the Universe became self-aware,’ suggests palaeontologist Simon Conway-Morris. ‘Creation [was] allowed by its Creator to make itself,’ argues physicist/theologian John Polkinghorne. Academically, such views are tolerated because they do not challenge the standard, atheistic view of the world and leave God as an optional extra; he plays no discernible role. Even though theologians pretend otherwise, scientists and laymen alike know that ‘creation’ means doing what nature itself cannot do.

(2) The diluvialist theory – defunct for over a century – was revived in 1961 by John Whitcomb and Henry Morris in their book The Genesis Flood. Their idea was that all fossil-bearing rocks were laid down in Noah’s Flood. They expected to be able to detect a pre-Flood surface that was overlain by catastrophic Flood deposits, whether the surface was buried and preserved or completely destroyed, leaving a gap. Fossilised terrestrial plants and animals would all have been transported from that original surface.

This theory is also not borne out. From the moment animals first appear, the geological record is stacked with living surfaces, both in marine and terrestrial settings, as is apparent from the reefs, animal tracks, burrows, droppings, nests and roots fossilised at countless horizons throughout the record. Each such surface was a fresh colonisation and the whole succession clearly occupied a substantial length of time.

How, then, should one explain the sequence of fossils, seeing that evolutionary lineages certainly do exist within the Phanerozoic sequence (whatever diluvialists may say)? If it is not a record of life gradually creating itself, nor a catastrophic record of organisms that perished in the Flood, two possibilities remain:

(3) The start of every apparently new lineage in the record represents a fresh act of creation – the view taken, for example, by 19th-century geologist Charles Lyell and 20th-century founder of ‘Reasons to Believe’, Hugh Ross. Commonly called progressive creationism, this is a theistic attempt to explain the fossil record. Whenever it proves difficult to connect a new form of life to a form that went before, God is inferred to have created the organism shortly before its appearance. The days of creation in Genesis are interpreted as aeons hundreds of millions of years long, with numerous creative interventions occurring at different moments in the course of each day. To quote an expositor of Ross, ‘God may have supernaturally intervened millions, possibly even billions, of times throughout the history of the universe.’ As the total number of species ever to have existed does not exceed billions, this comes very close to the fixity of species concept.

The explanation infers creation from biological design, but the acts of creation are now spread across the whole of history and have no chronological logic. If (as sometimes happens) a new discovery pushes back the first appearance of a species by tens of millions of years, God is assumed to have created the new form that much earlier. Moreover, whole groups of fossil organisms appear in an order different from that in which Genesis presents them, for example marine animals before seed plants and trees, while new species of marine animal continue to appear right through to the end. There was never a time when God rested. Not surprisingly, Darwin had little respect for this evolution-avoiding ad-lib invocation of the supernatural. ‘Do they really believe that at innumerable periods in the earth’s history certain elemental atoms have been commanded suddenly to flash into living tissues?’

It is also difficult to make sense of the creation of the Sun an entire aeon after photosynthesising plants and four aeons after the Earth. Reasons to Believe suggests that the Genesis passage should be re-translated. Others will see such contradictions as reasons not to believe, and as indications that the six days of creation cannot be interpreted as six distinct time-divisions of Earth history. It would be surprising if they could. Creation ought to have occurred in the beginning, not episodically throughout history.

The Intelligent Design movement constitutes a variant of this approach. But it avoids issues of scriptural interpretation, does not question the vast timescale of orthodox geology and is vague about how designed forms came into being. Worsted in a debate with Stephen Meyer and Rick Sternberg, the founder of The Skeptics Society, Michael Shermer, asked, “Well, what is your answer? How many acts of intelligence or creation – or whatever word you want to use – do you think happened? A scientist would want to know how did it happen, what is the actual mechanism of the Intelligence, the act of creation.” No answer was given.

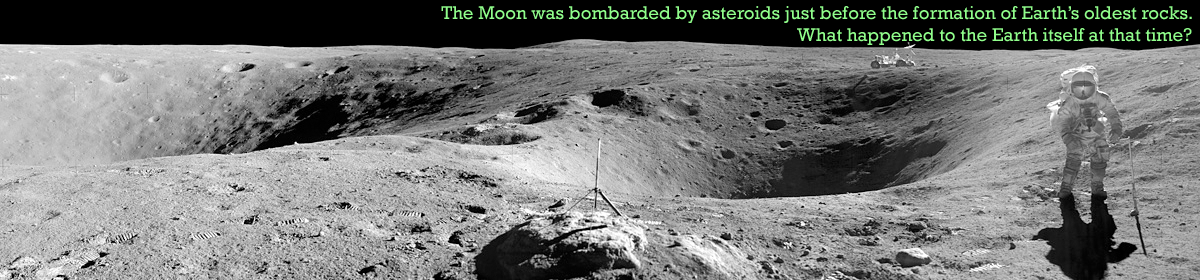

(4) The fossil sequence represents the recovery of marine and terrestrial populations after a cataclysm at the base of the geological record, some time after the creation of heaven and earth. The original landmass was destroyed by water rupturing it from below and asteroids from above, as attested to some extent geologically near the end of the Hadean and historically in folk traditions from all over the world, including Genesis.

The preserved history of the Earth begins immediately after the catastrophe, as magma surged towards the surface behind the released subterranean waters and renewed its crust. At this point the Earth was covered in ocean; there was almost no dry land. Fossils document the planet’s gradual recovery, beginning with bacteria and algae, in conditions that were to remain unstable for tens of thousands of years. Continental crust grew by volcanic processes, in the course of which it was repeatedly torn apart and reworked, layer upon layer. Environments changed and diversified, and as they adapted to them – not by any accidental process but along pathways controlled by their biological software – species, beginning from a small number of basic designs, also diversified.

The Hadean cataclysm was not the only global catastrophe in Earth history, albeit the first and by far the most deadly. A second occurred at the end of the Permian period and a third, only slightly less devastating, at the end of the Cretaceous. These mark respectively the end of the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic eras. Geologists divide the macrofossil record into the Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic precisely because of these catastrophes and the extinctions they caused. They had a profound effect on the history of life.

Thus at various points along the way (there were also lesser extinction events) Earth’s recolonisation was severely set back. At the end of the Permian, more than 90% of species are estimated to have gone extinct. The Hadean provides the context and some of the explanation for these later events. Earth has not always been as tranquil as in the last few thousand years, when man, taking advantage of its quietness, has completed the recolonisation process and built cities on it as if it would last forever.